Chance is the greatest novelist in the world.

Balsac

Vector Drawing made with an algorithm, based on Brownian Motion

Prelude: The Rhizome – the reordering of things

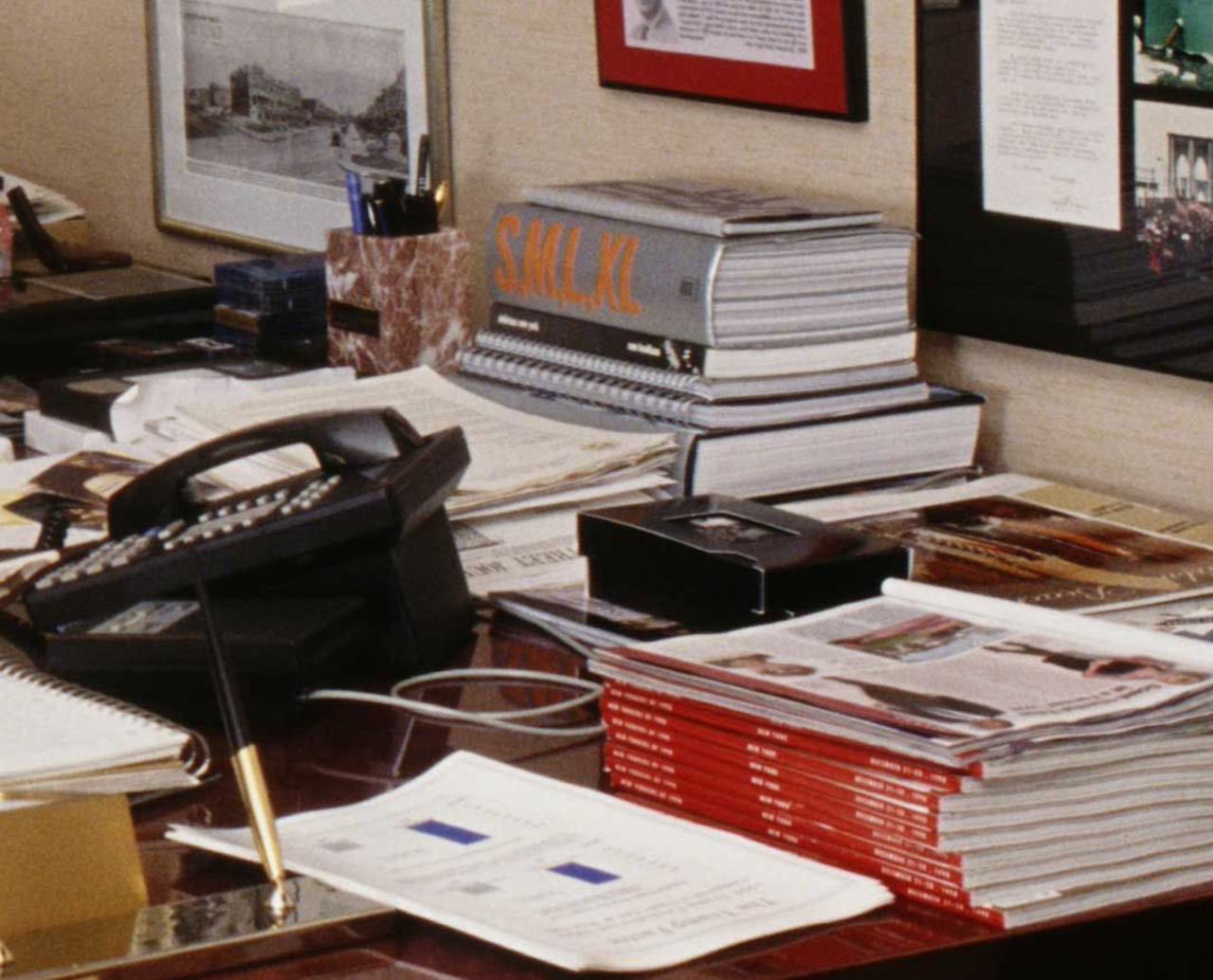

„This Massive Book is a Novel about Architecture“ is the first sentence on the back of S,M,L,XL, metallic-matte envelope, a book cover that engages its context, with reflections, dispersions and diffusions of light. The pages show an extensive accumulation of material produced by OMA. This material, whether previously published as independent essays or as documentation of theoretical and built projects, has been re-organized, re-positioned, re-related and re-framed into a new composite body. As a self-declared novel, this body of work makes no claim to the factual, but unfolds a range of subjectivities — from semiotic chains into a web of multiplicities. These semiotic chains are formed by sequences of images and texts: sometimes symbolic, sometimes indexical, sometimes images pose as text or text poses as image. These images and texts are subjected to a series of manipulations that operate an encyclopedic range of transformations1 performing extractions and integrations, dis-positionings and superimpositions — and, as a result, transversing information and weaving patterns. It “establishes connections between semiotic chains, organizations of power, and circumstances relative to the arts, sciences, and social struggles,”2 which, as the book cover states, “illuminates the condition of architecture today.”3

In short: it resembles the rhizome, a concept borrowed from botany and appropriated by Deleuze and Guattari in their book A Thousand Plateaus. Like S,M,L,XL, A Thousand Plateaus has no definite beginning or end, but is designed to allow a series of jumps through the text. Deleuze and Guattari use the term to describe a broader set of structural phenomena: they present the rhizome as a literary category, associate it with maps, and compare it to symbiotic relationships between distinct organisms, such as flowers and bees. In botany, the rhizome describes a network of roots, nodes and stems that enables the horizontal and independent proliferation of certain plant species. The roots build large underground networks, allowing plants to sprout from multiple locations, which in turn grow more roots. It is both a method of energy storage and a strategy of reproduction.4 The many different images, texts, and especially the dictionary in S,M,L,XL, and the multitude of their appearances, function as nodes: weaving lines of thought, linking ideas, people and places through associations, metaphors, resemblances and analogies.

The inclusion of a dictionary in the margins is probably the most noticeable feature of S,M,L,XL. The vast inclusiveness of S,M,L,XL and the integration of the dictionary recall the idea of the encyclopedia. Yet it converges the format of the encyclopedia with the literary character of the novel, the question of scientific objectivity with poetic subjectivities. It repeatedly brings together mathesis with poesis, it merges fact with fiction, analysis with imagination. The dictionary frees the signifier. The poly valence of S,M,L,XL and the heteroglossia1 of the dictionary might be regarded as a historical response to the paradigms of objectivity and functionality that had been brought forward inside the modern movement. S,M,L,XL is – in this sense – the product of the historical conscience of OMA and Rem Koolhaas. “The novel, however, not only does not require these conditions but (as we have said) even makes of the internal stratification of language, of its social heteroglossia and the variety of individual voices in it, the prerequisite for authentic novelistic prose.”

Between Mathesis and Poesis

The inclusion of a dictionary in the margins is probably the most noticeable feature of S,M,L,XL. The vast inclusiveness of the book and its integrated dictionary recall the idea of the encyclopedia, yet this encyclopedia format converges with the literary character of the novel, combining the question of scientific objectivity with poetic subjectivities. It repeatedly brings together mathesis with poesis, it merges fact with fiction, analysis with imagination. In doing so, the dictionary frees the signifier from the rigid fixity of conventional definitions. The polyvalence of S,M,L,XL and the heteroglossia5 of the dictionary can be regarded as a historical response to the paradigms of objectivity and functionality that had been brought forward inside the modern movement. S,M,L,XL is – in this sense – the product of the historical conscience of OMA and Rem Koolhaas.

Paris in the Sixties

Rem Koolhaas witnessed the architectural avant-garde shift its focus from the functional to the literary while working as a journalist and later joined this architectural discourse as an architect. Rem Koolhaas is said to have been in Paris at the time of the revolts in may 68 and as a journalist at a Dutch periodical: De Haagse Post he must have gotten into direct contact with the ideas of New Journalism.1 A few years later, in 1972, Rem Koolhaas was lecturing at Cornell, where he met Michel Foucault, became friends with Hubert Damisch and spend a year “immersed in French intellectual culture” after he had already spend considerable time researching Roland Barthes.2 His career began at a pivotal moment when ideas, movements, and figures in Paris reshaped the relationship between literature, theory, and architecture. In the early 1960s, Paris was a centre of intellectual thought, and several literary groups — such as Tel Quel, OuLiPo and the Situationists — were active in and around the city.

The first, Tel Quel, was a journal that published articles on both science and literature. Prominent contemporary thinkers and writers such as Roland Barthes, Jacques Derrida, Julia Kristeva, Gérard Genette, Georges Bataille, Umberto Eco and Michel Foucault found in the journal a platform for their ideas.1 Many contributions elevated literature to the status of a science and confronted science with the literary. The OuLiPo (Ouvroir de Littérature Potentielle) integrated mathematics into literature and set rules and constraints for the generation of texts. They also experimented with in situ (on-site) and in absentia (absent) forms of spatial writing. Georges Perec and Italo Calvino are perhaps its best-known members, the latter known for his eloquent combinatorics. Perec’s language, on the other hand, is characterised by evocations through seemingly objective descriptions.2 While, the Situationists, experimented with re-experiencing the city (dérive) and re-functioning existing images and texts (détournement). The movement, under the direction of Guy Debord, put forward a protest against the objectification of everyday life as a result of functionalistic modern culture. The three literary ensembles — Tel Quel, OuLiPo and the Situationists — each articulated different object–subject dispositions: Tel Quel through the association of science and literature; the Situationists through the propagation of subjective experience and the rejection of objects as art; OuLiPo through the combination of mathematical structure and literary narration. The dictionary in S,M,L,XL bears testimony to their influence. These differing approaches to objectivity and subjectivity—the scientific and the poetic, the structural and the experiential, the rule-bound and the spontaneous—are all echoed in the dictionary of S,M,L,XL.

The Limits of Classification

In 1962, Umberto Eco — medievalist, semiotician, novelist, contributor to

Tel Quel and friend of Michel Foucault — published Opera Aperta (The Open Work), a book in which he examines openness in texts and describes the concept as decisive for the possibilities of interpretation. The concept of openness is determined by the quantity and diversity of information — in other words, its semantic plurality. It can be understood as a constellation of positions within a field of relations, where the configuration of balance and disorder of information generates the poetic capacities within the text.

Michel Foucault, also a contributor to Tel Quel, published Les mots et les choses – une archéologie des sciences humaines (The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences) a few years later, in 1966. The book unfolds a genealogy of human knowledges, taking the 15th century as its starting point and tracing transformations of scientific understanding up to the turn of the 20th century. Foucault describes 15th-century modes of thought that are based on similarities and expressed through chains of associations. These modes shift towards a structural understanding of the world in differences, expressed through taxonomies and tables. Les mots et les choses describes and simultaneously questions the modalities and coherences of classifications — a central theme for the development of the sciences. Foucault compares and opposes modern scientific orders of classification to narrative and subjective structures of coherence that had been more prevalent in earlier epistemes. Foucault’s book describes a time when myth had a place alongside ratio, and a time when ratio became the dominant form of understanding. Earlier knowledge, as Foucault says, “therefore consisted in relating one form of language to another form of language; in restoring the great, unbroken plain of words and things; in making everything speak.”1 In other words, science tends to close rather than open the dialogic potential through its ambition to define.

It was in 1967, shortly after Foucault published The Order of Things, that Umberto Eco began to conceptualize semiotics in Appunti per una semiologia delle comunicazioni visive and delivered the infamous talk Towards a Semiological Guerrilla Warfare, where he proposed ways to subvert the media system through sabotage and the appropriation of the broadcasting system. This was an opposition to dominant modalities, advocating widespread appropriation of semiotic tools. In 1968, Eco published his first major work on semiotics, La struttura assente (The Absent Structure). This work emphasized the importance of multiplicity, plurality, and polysemy in art, highlighting the role of the reader in literary interpretation and the interactive process between reader and text.

May 1968

In May 1968, large civil protests erupted in the streets of Paris. The streets became a medium of communication through graffiti, with slogans such as “poetry is in the streets,” “a revolt against a technocratic system,” and “imagination is not a gift, it must be conquered” painted on public surfaces like the walls of the Odéon in Paris.

Many French theorists and writers—including Baudrillard, Lyotard, Virilio, Derrida, Foucault, Deleuze, and Guattari—participated in the protests.1 It was the rise and time of counter-culture.

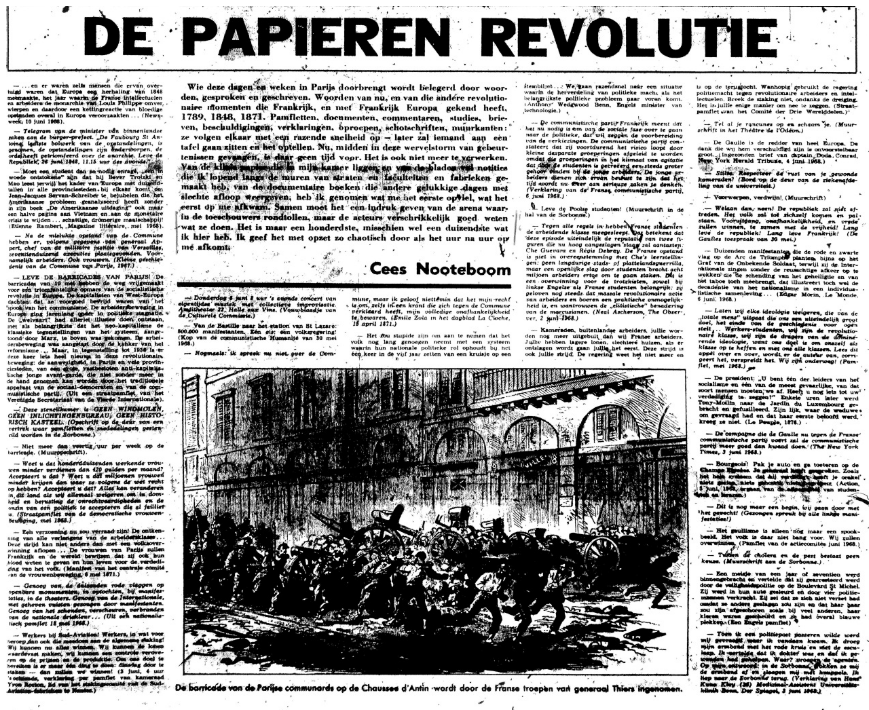

New Journalism emerged in the United States and challenged the dominant regime of journalistic objectivity. This movement propagated a style that valued the mediating qualities of subjective reporting. Exhibition venues for art and design, such as the Milan Triennale and Venice Biennale, were occupied; paintings were hung upside down and objects were turned around. Shortly after the protests, in 1969, the most important Dutch award for newspaper journalism was granted to Cees Noteboom for his report on the Paris revolts. Noteboom won the prize with an experimental compilation of collected captions (Image 2), quotes, and statements that emulated the diverse range of opinions and evoked the chaotic atmosphere surrounding those days.2

La condition postmoderne

La condition postmoderne: Rapport sur le savoir (The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge) published in 1979, Jean-François Lyotard suggests that “science has always been in conflict with narratives” 1 and argues that narrative knowledge fundamentally opposes scientific knowledge. This tension — often reduced to a commonplace feature of postmodernism — marks a defining element in the heterogeneity and contradictions of postmodern discourse itself. The dichotomy between narrative and scientific knowledge recurs in the positions taken by Tel Quel, in the constrained yet generative writing methods of OuLiPo, and in the Situationists’ activist tactics. In Les mots et les choses, Foucault similarly argues for the associative power of narrative modes of knowledge against the strict orders of classification imposed by science, while Umberto Eco’s idea of openness describes how a text’s semantic plurality expands its poetic capacity. Together, these French literary circles explored the fragile boundary between narrative and science through experimental writing and thematic transgressions, just as New Journalism broke open the scientific ideal of objectivity by weaving narration into reportage. Cees Noteboom’s exemplary reporting, composed as a bricolage of quotations and fragments, placed the responsibility for meaning on the reader and directly questioned the neutral role of the journalist.

Koolhaas deleuzianism

Most of the mentioned authors — Roland Barthes, Jacques Derrida, Julia Kristeva, Gérard Genette, Georges Bataille, Umberto Eco, and Michel Foucault — are quoted in the margins of S,M,L,XL. Their quotations represent both explicit and implicit concepts.1 The most significant idea might be one based on a specific botanical category: the rhizome. This concept was introduced by Deleuze and Guattari and published in Mille Plateaux: Capitalisme et Schizophrénie (A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia) in 1987, a few years before the publication of S,M,L,XL.2 The metaphor of the Rhizome describes – among others – the structural proliferation of knowledge through associations. Proliferations that are neither linear nor tree-like.3 It is a structure of thought that harnesses poetic registers through openness. The rhizome proposes a mode of thought where everything speaks, and disciplinary boundaries—or indeed any boundaries—are deterritorialized.

Formal and structural comparisons between the rhizome and the architecture of OMA are not new and Rem Koolhaas himself has uttered the fear of becoming Deleuzian, expressing that it “might already be to late”4 Added to that, S,M,L,XL seems close to definition of the ideal book that Deleuze propagates: “The ideal for a book would be to lay everything out on a plane of exteriority of this kind, on a single page, the same sheet: lived events, historical determinations, concepts, individuals, groups, social formations.“5

Footnotes

S,M,L,XL is a book by Rem Koolhaas and Bruce Mau, edited by Jennifer Sigler, with photography by Hans Werlemann.